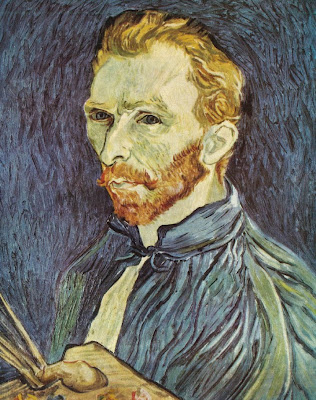

“It is like the pollard willows of our Dutch meadows or the oak bushes of our dunes; the rustle of an olive grove has something very secret in it, and immensely old. It is too beautiful for us to dare to paint it or to be able to imagine it.”

*Letter from Vincent Van Gogh, May 1, 1882 (1)

“There was something that lurked in the dark. It could not be imagined. It could not be described.”

“There was something that lurked in the dark. It could not be imagined. It could not be described.”

*The Monster from Earth’s End (2)

Amid the cabbage plants, mosses and lichens, tussock grass, stunted forest tangled with daisies and buttercups, something else spread across the tundra of Gow Island in 1959. The violence, insanity and horror that steadily took over there appealed to director Michael Hoey who confessed, “Around 1959, I read a book called The Monster from Earth’s End by Murray Leinster. I was very taken with it and thought, ‘Gee, this could be an exciting film.’” (3)

The administrating officer, Drake, tries to remain rational throughout his experience on the small island, “In a real world, everything follows natural laws. Impossible things do not happen. There is an explanation for everything that does happen.” (4) Despite such assurance, Drake begins to slip and admits to himself, “On the other hand, if something sufficiently unlikely occurred, he might disbelieve the evidence of his senses. He might become convinced of his own insanity. He could act on the assumption that he himself had gone mad.” (5) As people, dogs and birds die and fear takes over, it becomes clear that existence is as much a battle for sanity as it is a battle against an unknown terror. Drake insists, “But I’ve been having all the experiences of a madman. I’ve got to be a little bit stern and make him tell his hallucinations. They may not be delusions. Maybe they’re facts. On this island you can’t use the standards of a sane world to decide what’s crazy and what isn’t!” (6) What caused such a collapse and unleashed the hysteria and bloodshed to follow? The sight of trees…

The administrating officer, Drake, tries to remain rational throughout his experience on the small island, “In a real world, everything follows natural laws. Impossible things do not happen. There is an explanation for everything that does happen.” (4) Despite such assurance, Drake begins to slip and admits to himself, “On the other hand, if something sufficiently unlikely occurred, he might disbelieve the evidence of his senses. He might become convinced of his own insanity. He could act on the assumption that he himself had gone mad.” (5) As people, dogs and birds die and fear takes over, it becomes clear that existence is as much a battle for sanity as it is a battle against an unknown terror. Drake insists, “But I’ve been having all the experiences of a madman. I’ve got to be a little bit stern and make him tell his hallucinations. They may not be delusions. Maybe they’re facts. On this island you can’t use the standards of a sane world to decide what’s crazy and what isn’t!” (6) What caused such a collapse and unleashed the hysteria and bloodshed to follow? The sight of trees…

“Its actual appearance in that place was as if some insane artist had traveled thousands of miles to create.”

*The Monster from Earth’s End (7)

“As for me, I tell you as a friend, I feel impotent when confronted with such nature, for my Northern brains were oppressed by a nightmare in those peaceful spots, as I felt that one ought to do better things with the foliage.”

*Letter from Vincent Van Gogh, 1889 (8)

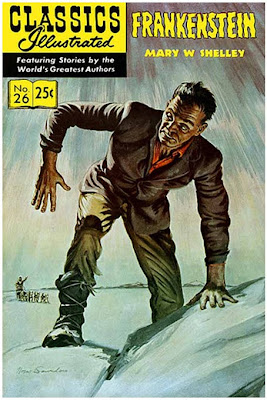

If only Drake and the others trapped on Gow had been aware of a parallel place with an open door to their shadows. Thousands of miles away on the mirror other side of the world lies the North Pole, “that enchanted continent in the sky, land of everlasting mystery.” (9) Long a land of free imagination, this arctic source of myth and legends includes the horror of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In 1818 she set the scene: “I feel a cold northern breeze play upon my cheeks…Inspirited by this wind of promise, my daydreams become more fervent and vivid. I try in vain to be persuaded that the pole is the seat of frost and desolation; it ever presents itself to my imagination as the region of beauty and delight…there snow and frost are banished; and, sailing over a calm sea, we may be wafted to a land surpassing in wonders and in beauty every region hitherto discovered on the habitable globe.” (10)

If only Drake and the others trapped on Gow had been aware of a parallel place with an open door to their shadows. Thousands of miles away on the mirror other side of the world lies the North Pole, “that enchanted continent in the sky, land of everlasting mystery.” (9) Long a land of free imagination, this arctic source of myth and legends includes the horror of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In 1818 she set the scene: “I feel a cold northern breeze play upon my cheeks…Inspirited by this wind of promise, my daydreams become more fervent and vivid. I try in vain to be persuaded that the pole is the seat of frost and desolation; it ever presents itself to my imagination as the region of beauty and delight…there snow and frost are banished; and, sailing over a calm sea, we may be wafted to a land surpassing in wonders and in beauty every region hitherto discovered on the habitable globe.” (10) This vision became part of Admiral Byrd lore when the polar explorer hinted at greater mysteries in 1947, “I’d like to see the land beyond the Pole. That area beyond the Pole is the center of the great unknown.” (11) There are rumors that Byrd found that ‘center of the great unknown’ and even flew inside to explore, landing and finding that both poles have holes leading into the Hollow Earth.

This vision became part of Admiral Byrd lore when the polar explorer hinted at greater mysteries in 1947, “I’d like to see the land beyond the Pole. That area beyond the Pole is the center of the great unknown.” (11) There are rumors that Byrd found that ‘center of the great unknown’ and even flew inside to explore, landing and finding that both poles have holes leading into the Hollow Earth. Already revealed in Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, Oz historian L. Frank Baum also used this location for Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, published in 1908. Dorothy says, “We are somewhere in the middle of the earth, and the chances are we’ll reach the other side of it before long. But it’s a big hollow, isn’t it?” (12) She and her traveling companions observe, “On some of the bushes might be seen a bud, a blossom, a baby, a half-grown person and a ripe one.” (13) It doesn’t take long before one of these plant creatures threatens them with a cruel death.

Already revealed in Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, Oz historian L. Frank Baum also used this location for Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, published in 1908. Dorothy says, “We are somewhere in the middle of the earth, and the chances are we’ll reach the other side of it before long. But it’s a big hollow, isn’t it?” (12) She and her traveling companions observe, “On some of the bushes might be seen a bud, a blossom, a baby, a half-grown person and a ripe one.” (13) It doesn’t take long before one of these plant creatures threatens them with a cruel death. Then in 1951, a long flight from Alaska, “Botanists, physicists, including a pin-up girl” were at war with “Our superior in every way…a being from another world, as different from us as one pole from another.” The Thing from Another World revealed, “an intellectual super-carrot” from the crashed ice remains of a flying saucer. The North Pole base came under attack, dogs were mauled. Presiding Captain Patrick Hendry gathered the forces, arming his fellows with weapons, guns, gasoline and electricity.

Then in 1951, a long flight from Alaska, “Botanists, physicists, including a pin-up girl” were at war with “Our superior in every way…a being from another world, as different from us as one pole from another.” The Thing from Another World revealed, “an intellectual super-carrot” from the crashed ice remains of a flying saucer. The North Pole base came under attack, dogs were mauled. Presiding Captain Patrick Hendry gathered the forces, arming his fellows with weapons, guns, gasoline and electricity.In opposition to the vigilante mentality, scientist Dr. Carrington is committed to keeping a sane approach to the escalating violence. It is his goal to study the creature.

He decides “science rather than the army” should lead. Even in the face of death, he is sure, “Knowledge is more important than life.” So it is a pivotal moment when he introduces himself to the Frankenstein-like monster in a dark Quonset hallway with, “You’re wiser than anything on Earth—” only to get clubbed to the slatted floor. Like the night crawling menace of Gow Island, the Thing is also a deadly plant creature that lives on blood.

He decides “science rather than the army” should lead. Even in the face of death, he is sure, “Knowledge is more important than life.” So it is a pivotal moment when he introduces himself to the Frankenstein-like monster in a dark Quonset hallway with, “You’re wiser than anything on Earth—” only to get clubbed to the slatted floor. Like the night crawling menace of Gow Island, the Thing is also a deadly plant creature that lives on blood. Inspired by The Thing from Another World, director Michael Hoey bought the rights to The Monster from Earth’s End in 1961 “for a horrendous sum, like around $4,000.” (14) Yet it took until 1966 to be filmed and Hoey sadly confirms the result, “By the time the film was completed, I would have been ashamed to talk to [the author] because of what happened.” (15) In any case…

“When I bought the book, I thought, ‘Monster from Earth’s End’…that’s too exploitative a title. I’d like another title.’ One day I’m driving down the street and I see a sign on some guy’s lawn, NIGHTCRAWLERS FOR SALE. Obviously he was talking about worms, but I thought, ‘Boy, that’s a great title for this project!’ So I called it The Nightcrawlers. But Jack Broder, who was the executive producer, retitled it The Navy vs. the Night Monsters, which is an abominable title. I remember the day when I was rehearsing and Broder walked in and announced what the new title was going to be. The entire cast was ready to walk out—they were furious that he would give it that title. Such an exploitative, dumb title.”

*Michael A. Hoey (16)

“The picture is one of the ugliest I have done…I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green.”

*Letter from Vincent Van Gogh, 1888 (17)

A painted sunset or sunrise appears as an orange and blue canvas backdrop for the words, The Navy vs. the Night Monsters, and actor names. “I have observed that a very simple flat frame in vivid orange lead would produce the desired effect in conjunction with blues of the background and the dark green of trees.” (18) The picture fades in favor of a narration intoned over a bleak collection of stock footage ice, “Antarctica, the frozen continent at the bottom of the world. A continent as mysterious and unknown as the other planets of our solar system. Or a world in deep space a million light years away.” But the movie takes place on a tropical island. Gow Island resembles California or Vietnam.

Like the script of a paperback left out in the rain, the movie follows a warped version of the book. It seems clear that the film is directed more at a teenage Drive-In audience, especially with its mordant jokes about egg salad, balloons and girls. The sitcom atmosphere is quickly shattered though when death arrives whistling like a tea kettle in the night.

Antarctic trees crash land on Gow and begin to stalk. “It was a living fossil, with a basic structure remote from all experience. Its cellulose fibers were extraordinarily long. They were oriented like flax-fibers, from which linen is made.” (19) The sight of it is so terrifying to the people in the movie that their reaction may seem strange. Their horrific tortured nightmare of the psyche comes across in today’s light as a walking, sprouting sleeping bag. This didn’t go unnoticed by the director though. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Michael Hoey describes the film as a battle between his vision and the budget, but more specifically a war with his ham-fisted producer Jack Broder.

Jack Broder had ultimate control over the final cut. After Hoey turned in his reels and went to San Francisco to begin shooting Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine, Broder added 12 minutes to the running time to market the film for television. 720 more seconds result in a lot of comic book scenes, Mamie Van Doren’s blueprint dress, a beach full of tree stumps crawling, but the most surreal touch is saved for the closing moments, in the napalmed jungle finale: “The picture ends with a stock shot with the four Blue Angels, with multi-colored streamers going out the back. No combat plane in its life ever did anything like that! It was footage from an air show. The logic that went into it was almost non-existent!” (20)

Hoey had his own artistic logic, “The premise that I functioned under was ‘less is more,’ and if you don’t show it, the audience’s imagination would create a much more vivid monster than we could ever create visually.” (21) The breaking point for him was the sight of the trees. “I wanted the trees to look like the other trees, so that there wouldn’t be the feeling that they stood out like sore thumbs, which is what those stupid things did. Broder hired some guy who did them for $1.98. When they showed up on the set the first day, I refused to film them, I was so upset.” (22) Broder vs. Hoey was a contrast as polar as night and day and it literally came down to that in the filming of the trees. “They brought in one tree where a guy could get inside and wiggle his arms, and two other ‘dummy’ trees which just stood there. Stanley Cortez and I looked at each other and said, ‘How are we gonna shoot this?’, and I said, ‘How ‘bout no lights?’ And he said, ‘Well, that’s probably the only way we can do it.’ So we literally tried to light it so that it was so dark that the only time you would see the trees was when the Molotov cocktails were exploding around them. Well, Broder didn’t like that and he had that scene ‘printed up’ [brightened] so that the trees are vividly lit. But that was never our intention of how we would show ‘em.” (23)

“I can’t imagine a thing which prefers darkness attacking things because they’re light.”

*The Monster from Earth’s End (24)

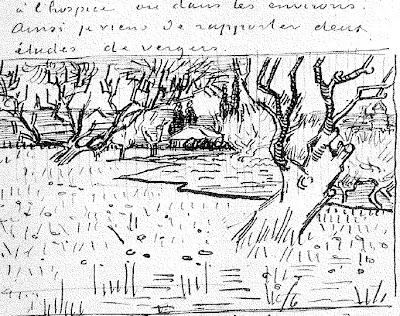

In fact, it could be one of those trees! The way Van Gogh portrays them fits perfectly:

In fact, it could be one of those trees! The way Van Gogh portrays them fits perfectly: “The Roots shows some tree roots on sandy ground. Now I tried to put the same sentiment into the landscape as I put into the figure: the convulsive, passionate clinging to the earth, and yet being half torn up by the storm. I wanted to express something of the struggle for life... in the black, gnarled and knotty roots.” (25)

Also, compare the pastels of the Nightcrawlers’ jungle to the Night Café:

“The fact is that the sun has never penetrated us people of the North…a street stretching away under a blue sky spangled with stars…dark blue or violet and there is a green tree. Here you have a night picture without any black in it, done with nothing but beautiful blue and violet and green, and citron-yellow color.” (26)

And the big screen repeats the view out his asylum window:

“These high trees stand out against an evening sky with violet stripes on a yellow ground, which higher up turns into pink, into green…Now the nearest tree is an enormous trunk, struck by lightning and sawed off. But one side branch shoots up very high and lets fall an avalanche of dark green pine needles. This somber giant—like a defeated proud man—contrasts, when considered in the nature of a living creature, with the pale smile of a last rose on the fading bush in front of him. Underneath the trees, empty stone benches, sullen box trees; the sky is mirrored—yellow—in a puddle left by the rain. A sunbeam, the last ray of daylight, raises the somber ocher almost to orange. Here and there small black figures wander around among the tree trunks.” (27)

“These high trees stand out against an evening sky with violet stripes on a yellow ground, which higher up turns into pink, into green…Now the nearest tree is an enormous trunk, struck by lightning and sawed off. But one side branch shoots up very high and lets fall an avalanche of dark green pine needles. This somber giant—like a defeated proud man—contrasts, when considered in the nature of a living creature, with the pale smile of a last rose on the fading bush in front of him. Underneath the trees, empty stone benches, sullen box trees; the sky is mirrored—yellow—in a puddle left by the rain. A sunbeam, the last ray of daylight, raises the somber ocher almost to orange. Here and there small black figures wander around among the tree trunks.” (27)

This is the sight of trees that haunted Gow Island, painted with the vision of one haunted by worse monsters as he went out in his last days:

“A man called Jullian, who in later life went on to be the municipal librarian, recalled with shame how as a youth he had taken part in the baiting: ‘I remember—and I am bitterly ashamed of it now—how I threw cabbage-stalks at him! What do you expect? We were young, and he was odd, going out to paint in the country, his pipe between his teeth, his big body a bit hunched, a mad look in his eye.’” (28)

Footnotes (Stock Footage)

1) Dear Theo, The Autobiography of Vincent Van Gogh; Edited by Irving

Stone; Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston; 1937; p. 504

2) The Monster from Earth’s End, by Murray Leinster; Gold Medal Books;

Fawcett Publications Inc. Greenwich Conn. 1959; p. 79

3) I Was a Monster Movie Maker: Conversations with 22 SF and Horror

Filmmakers, by Tom Weaver; McFarland & Co. Inc. Jefferson, NC,

2001; p. 96

4) The Monster from Earth’s End, by Murray Leinster; Gold Medal Books;

Fawcett Publications Inc. Greenwich Conn. 1959; p. 92

5) Ibid., p. 32

6) Ibid., p. 135

7) Ibid., p. 154

8) The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Volume Three, New York

Graphic Society, Greenwich, Connecticut, 1958; p.232

9) As quoting Admiral Byrd; The Hollow Earth, The Greatest Geographical

Discovery in History, Made by Admiral Richard E. Byrd in the

Mysterious Land Beyond the Poles—The True Origin of the Flying

Saucers; by Dr. Raymond Bernard; Bell Publishing Company; NY;

1969; p.20

In 1947, “Before he left on his seven hour flight from his Arctic base over iceless land beyond the North Pole (leading to the interior of the Earth), Admiral Byrd said: ‘I would like to see that land beyond the Pole. That area beyond the Pole is the center of the Great Unknown.’ Admiral Byrd did not cross over the North Pole and travel 1,700 miles south on its other side. If he did, he would enter icebound territory. Instead he entered a land with a warmer climate, free from ice and snow, consisting of forests, mountains, lakes, green vegetation and animal life. This new unknown land over which he flew for 1, 700 miles, which was not on any map, existed inside the polar opening leading to the hollow interior of the Earth, where it is warmer than on its outside, which is here a land of ice and snow.” (29)

In 1947, “Before he left on his seven hour flight from his Arctic base over iceless land beyond the North Pole (leading to the interior of the Earth), Admiral Byrd said: ‘I would like to see that land beyond the Pole. That area beyond the Pole is the center of the Great Unknown.’ Admiral Byrd did not cross over the North Pole and travel 1,700 miles south on its other side. If he did, he would enter icebound territory. Instead he entered a land with a warmer climate, free from ice and snow, consisting of forests, mountains, lakes, green vegetation and animal life. This new unknown land over which he flew for 1, 700 miles, which was not on any map, existed inside the polar opening leading to the hollow interior of the Earth, where it is warmer than on its outside, which is here a land of ice and snow.” (29) 10) Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley; Viking, New York; 1998, p. 11

11) The Hollow Earth, The Greatest Geographical Discovery in History, Made

by Admiral Richard E. Byrd in the Mysterious Land Beyond the

Poles—The True Origin of the Flying Saucers; by Dr. Raymond

Bernard; Bell Publishing Company; NY; 1969; p. 44

12) Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, by L. Frank Baum; Books of Wonder,

Harper Collins Publishing; 1990; p.28

13) Ibid.

14) I Was a Monster Movie Maker: Conversations with 22 SF and Horror

Filmmakers, by Tom Weaver; McFarland & Co. Inc. Jefferson, NC,

2001; p. 98

15) Ibid., p.97

16) Ibid., p.98

17) Stranger on the Earth; a Psychological Biography of Vincent Van Gogh, by

Albert J. Lubin; New York, Holt, Rineheart Winston; 1972; p.142

18) The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Volume Three, New York

Graphic Society, Greenwich, Connecticut, 1958; p.258.

19) The Monster from Earth’s End, by Murray Leinster; Gold Medal Books;

Fawcett Publications Inc. Greenwich Conn. 1959; p.62

20) I Was a Monster Movie Maker: Conversations with 22 SF and Horror

Filmmakers, by Tom Weaver; p.106

21) Ibid.; p.102

22) Ibid.; p.104

23) Ibid.; p.104

24) The Monster from Earth’s End; p. 49

25) The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Volume One, New York

Graphic Society, Greenwich, Connecticut, 1958; p.360

26) The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Volume Three; p.444

26) The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Volume Three; p.444 27) Ibid.; p. 524

28) Van Gogh, His Life and His Art; David Sweetman; Crown Publishers, Inc.

New York; 1990; p.299

29) The Hollow Earth, The Greatest Geographical Discovery in History, Made

by Admiral Richard E. Byrd in the Mysterious Land Beyond the

Poles—The True Origin of the Flying Saucers; p.24

Featuring Quotes from Films:

The Thing from Another World (1951)

The Navy vs. the Night Monsters (1966)

“Gow Island. In the past, virtually unknown to the rest of the world. Today, a famous landmark in man’s struggle with the unknown. Another step forward in the march of science.”

Essay by Allen Frost

No comments:

Post a Comment